Appendix

A

LITERATURE SEARCHES

Introduction

A review of the literature is an essential component of any research study. This appendix summarizes the sources of information and the strategies for identifying and obtaining relevant materials. Details on how to report a literature review, and the format for citations, are given in Chapter Six.

Any research study must build on what is already known. A literature review enables a person to gain an understanding of the topic and become familiar with the existing state of knowledge. It will identify related research and data so that proposed research can be placed in perspective. A review of the literature might even provide the answers to the problem at hand, such that further investigation is unnecessary. There is so much information available that a critical analysis of the state-of-the-art can be a very cost-effective method of solving problems. Where the review is a prelude to experimental work, the review might identify unanticipated problems, and sometimes, the solutions. Above all, a thorough review of the literature ensures that the proposed study will meet accepted standards and not waste resources.

The vast body of information now available is both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, there is a greater chance of finding the desired information; on the other hand, the sheer volume of the literature can be intimidating. Fortunately, the development of modern computers and electronic databases has made searching the literature a much simpler task than in the days of color-coded index cards and mechanical systems which relied upon the use of cards with holes punched according to coding system.

There are two types of electronic databases: bibliographic and full text. Bibliographic databases provide complete reference information on an article, including title, author, publication, and date. Some bibliographic databases, such as TRIS (see section later in this appendix) also include an abstract of the article. Full text databases provide access to the full text of an article, but are usually much narrower in scope than bibliographic databases.

Searching the literature involves two essential steps:

1. Identifying relevant articles

2. Obtaining a copy of the articles.

While the creation of numerous databases, and the existence of the Internet, has opened up many new sources of information to the researcher, it has also increased the importance of the professional librarian. Access to many of the commercial databases is expensive, and time on-line must be kept to a minimum. Furthermore, most libraries lend materials only to patrons and to other libraries, and consequently the assistance of a librarian is needed to borrow any materials from collections outside one’s home library.

Sources of Information

Although the technology for searching the literature has changed dramatically in recent years, the principles have not. The basic rule is to progress from the general to the specific as illustrated in Figure B-1. The point at which one begins the search depends upon one’s level of knowledge on the subject at hand.

Encyclopaedias are the most general sources of information and, for situations where the researcher is new to the field, a surprisingly useful way of gaining an introduction and some understanding of a subject. Books constitute the next level of specialization and provide a more detailed treatment than is possible in an encyclopaedia. Books are valuable in that they usually provide a balanced treatment of a subject, though their relevance depends on the date of publication and the particular subject matter. If one is fortunate to find a recent monograph, this can be very helpful. The inherent disadvantage of any textbook is that a long time is required for writing, editing and publication. This inevitably means that the text will not be up-to-date, even on the day of publication. In fields that are changing rapidly, such as instrumentation, computer hardware and computer applications, textbooks can provide only an introduction to the subject and most of the required information must be obtained from recent journals, papers, and periodicals.

Hierarchy of Sources | Hierarchy of Searching |

|

|

Encyclopaedias | Titles |

Textbooks | Key Words |

Abstracts | Abstracts |

Journals | Documents |

Conference Proceedings |

|

Periodicals |

|

Reports |

|

Trade Literature |

|

Personal Contacts |

|

Figure A -1: Hierarchies of Sources and Searching

In most fields of science and engineering, abstracts of recent publications are available from commercial sources. Subscriptions are expensive, and commercial abstracts are therefore usually found only in libraries. The simplest compilations publish the titles, abstracts and keywords (as provided by the author) of articles published in a specified number of journals and periodicals. More sophisticated abstracts provide keywords assigned by professional indexers, translations of abstracts published in foreign languages, and, sometimes, annotated summaries. Commercial abstracts are often the best method of searching foreign language publications if one does not know the language.

Journals are one of the most important sources of information. They are normally peer-reviewed, which assures the quality of the publication, and each article contains a list of references for which there are full citations. A review article, especially one that is recent, is particularly useful, not only for the review, but also for the list of references. For most subject areas, the researcher will find that a substantial proportion of the most relevant articles are published in a relatively small number of journals. Having identified these journals, concentrating one’s efforts on recent issues can be an effective way of locating the most useful articles.

Papers published in conference proceedings can also be useful in providing details of recent research or work-in-progress, but they tend to be more difficult to identify and obtain than journal articles. Because conference proceedings are often not subject to peer review, the quality of the papers may be uneven. Papers contained in conference proceedings do not always appear in electronic databases. Where the proceedings are published by a commercial publisher or technical society, they can be purchased or obtained through an interlibrary loan without difficulty. Where the proceedings are published by the conference organizers, and distributed only to the delegates, copies may not be available.

Articles published in periodicals differ from papers in journals in that they are usually chosen to be of general interest, and consequently are written in a more journalistic style and provide fewer technical details. The articles usually describe recent events and are an excellent way of finding out what is happening in the field of interest.

Reports are similar to conference proceedings in that they are not always catalogued, the quality is uneven, and they may be difficult to obtain. The situation improved considerably in the transportation field with the requirement that all reports be catalogued in the TRIS database, and can usually be obtained from either the sponsor or the National Technical Information Service (NTIS), Springfield, VA 22161. The advantage of reports is that they provide the most complete record of a research study. Theses also provide complete documentation of studies, and are available from the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor.

Trade literature should not be discounted as a useful source of information, particularly for details of new materials, products, and equipment. Providing the reader is alert for bias and lack of objectivity, trade literature has the advantages of describing practical applications, and being up-to-date.

The most direct method of obtaining information is to write or speak to the author of an article or a researcher who is currently working in the area of interest. While most researchers are willing to discuss work that has been published, and often provide details of work-in-progress, contact should not be made until you have prepared adequately. Direct personal contact is usually not appropriate until you understand the subject and are familiar with the previous work of the researcher. Questions should be direct and specific. Vague, general questions are unlikely to lead to fruitful discussion because no one has the time to explain what you should be capable of finding out for yourself.

The literature is so vast that it is never possible to locate all the relevant articles on a topic. The objectives of the literature search should be to gain an understanding of the subject matter, and to read the most relevant articles that are obtainable. The “obtainable” criterion should not be interpreted as an excuse not to be persistent in locating copies of relevant articles from obscure sources!

Search Hierarchy

As with sources of information, the hierarchy of searching progresses from the general to the specific, in a logical series of steps. Each step is followed by a selection process. While the steps have become blurred with the advent of electronic searching, the principles remain.

In the past, catalogues would be searched for the titles of articles that appeared relevant, by searching for key words. Abstracts of the most relevant articles would be obtained, and a decision made whether to obtain a copy of the document, depending upon the relevance of the abstract, and the location of the document. This is a very important activity because a lot of time and money can be wasted obtaining documents that ultimately prove not to be very useful. Electronic searches typically search for key words in titles, key word indexes and abstracts simultaneously. In a situation where a very large number of “hits” occurs, it is usually worthwhile to scan the titles manually, before printing the abstracts, because it may be obvious that many of the titles are not relevant. A similar review should be made of the abstracts before documents are ordered.

If you have access to a good technical library, the time-honored pastime of browsing the collection is often time well spent. It is surprising how often very relevant articles are discovered which have not been identified by searching databases. Most library information is catalogued according to one of two major systems: the Library of Congress System or the Dewey Decimal System. The main categories of these two systems are given in Tables A-1 and A-2. The main categories are subdivided several times into areas and subjects such that each publication has a unique call number, which determines its location in the stacks. This means that related material appears in the same location, so that if browsing locates one useful article, others may be close-by.

Journals are not often catalogued, but are shelved alphabetically by title. As noted in the previous section, articles relevant to a particular field of study tend to be published in a small number of journals. Once the journals have been identified, browsing through recent issues can be the beginning of a very rewarding trail. Checking the list of references in recent articles, and subsequently checking the reference lists in those articles, often leads to the identification of a significant portion of the literature.

Table A-1: The Dewey Decimal System

000 General Works |

500 Natural Science |

100 Philosophy |

600 Useful Arts |

200 Religion |

700 Fine Arts |

300 Sociology |

800 Literature |

400 Philology |

900 History |

Table A-2: The Library of Congress System

A |

General Works |

M |

Music |

B |

Philosophy, Religion |

N |

Fine Art |

C |

History |

P |

Language and Literature |

D |

Foreign History |

Q |

Science |

E, F |

American History |

R |

Medicine |

G |

Geography, Anthropology |

S |

Agriculture |

H |

Social Science |

T |

Technology |

J |

Political Science |

U |

Military Science |

K |

Law |

V |

Naval Science |

L |

Education |

Z |

Library Science |

Search Strategies

Most online searches rely on the use of the Boolean operators AND, OR, NOT, often in conjunction with parentheses. The Boolean operators are not intuitive. For example AND does not add terms to create a greater sum (as in “I will have bacon and eggs”). The OR connector does not reduce the sum (as in “I will have bacon or eggs”). In Boolean Logic the opposite happens, AND reduces, OR expands. The operators are illustrated pictorially in Figure A-2, and examples are given later in this section.

Figure A-2: Illustration of Boolean Operators

There are a number of simple rules for improving the effectiveness of searches, and minimizing the amount of time online.

a) Be specific

The more specific the topic, the lower the probability of identifying articles which are not relevant. For example, a topic such as ‘Waterproofing Membranes for Concrete Bridges’ provides four words that define a precise area of search. Conversely, a search to identify the literature relevant to the writing of this manual is difficult because the topic is so broad and key words such as science, research, transportation, and methodology can be used in several contexts. In such a case, it is advisable to conduct a series of searches on narrower topics, such as the subject of each chapter.

b) Simplify

Use only key words, and eliminate prepositions, articles and connecting words such as the, and, for, at, by, to, with. Most databases prohibit the use of common prepositions and the Boolean operators as search terms. TRANSPORT (explained in the next section) prohibits the use of a, an, and, in, not, near, of, on, or, the, with.

c) Retrieve only the most recent articles

Most databases allow for the retrieval of articles published after a specified date. The most difficult part of any literature search is obtaining the first few “hits”. As noted in the section ‘Sources of Information’, a recent article is often a gateway to the most relevant literature. Concentrating on the most recent literature also enables the searcher to try different approaches and keywords without the expense of identifying a large body of literature that is not relevant.

d) Truncate

Truncate words to retrieve all words that begin with the same letters. For example:

scien* (the wild card or truncation symbol * is used in TRANSPORT) will retrieve articles containing the words science, scientific and scientist.

e) Ignore Uppercase Letters

Most databases are not case sensitive and all keywords can be entered in lowercase letters, including proper nouns.

f) Use AND to narrow a search

For example waterproof* AND membrane* will retrieve only items which include waterproof (and waterproofing) and membrane (and membranes), i.e. it will exclude waterproof sealers and admixed waterproofers (because they are not membranes). A search of waterproof* AND membrane* AND bridge will exclude applications to structures such as parking garages and tunnels from the previous search. By narrowing the search to waterproof AND membranes AND bridge AND concrete, applications to steel and timber bridges will be excluded. However, there is a danger in making the search too narrow, because applications to concrete bridges will also be excluded, unless the author included the word “concrete” in the keywords or abstract (depending on the database).

g) Use OR to broaden a search

This technique is particularly useful when different terms are used for the same thing. For example, in a search for articles on elastomeric bearings, the keywords would probably be bearing AND elastomer OR rubber.

h) Use NOT to exclude a concept

For example, if one is interested in bearings used in static applications such as bridges and machinery bases, but not dynamic applications such as automobile engine mounts or helicopter rotors, the search might be bearing AND (bridge OR machine) NOT (engine OR rotor). The use of the parentheses is significant. The above will retrieve every article that includes “bridge” or “machine”, in combination with “bearing”, provided it does not also contain the word “engine” or “rotor”.

TRANSPORT also recognizes the search operators NEAR, WITH and IN. NEAR finds records that contain two terms within the same sentence, e.g. “speed” and “bump”. The addition of a numeral, e.g. NEAR4 finds terms within the specified number of words of each other. NEAR can be used very effectively to locate terms which usually appear together, e.g. speed NEAR2 (bump OR hump) OR rumble strip will produce a search that locates all articles which contain speed bump, speed hump OR rumble strip (or the plurals of these terms).

The operator WITH is used to find records that contain two (or more) terms in the same field. The fields in TRANSPORT are given in Table A-3.

IN is used to limit a search to words in a particular field. For example Smith IN AU would identify all the articles written by anyone called Smith.

Table A-3: Fields in TRANSPORT

AB | Abstract |

AU | Author |

CA | Corporate Author(s) |

CN | Internal Control Number |

DE | Descriptors |

IS | ISSN Number |

LA | Language of Document |

LS | Language of Summary |

NT | Source Notes |

PA | Publication Availability |

PB | Publishers |

PY | Publication Year |

RN | Report Number |

RS | Record Source |

SB | Subfile |

SC | Subject Classification |

SO | Source (Publication Title) |

TI | Title |

UD | Update Code |

Transportation Research Information Services (TRIS)

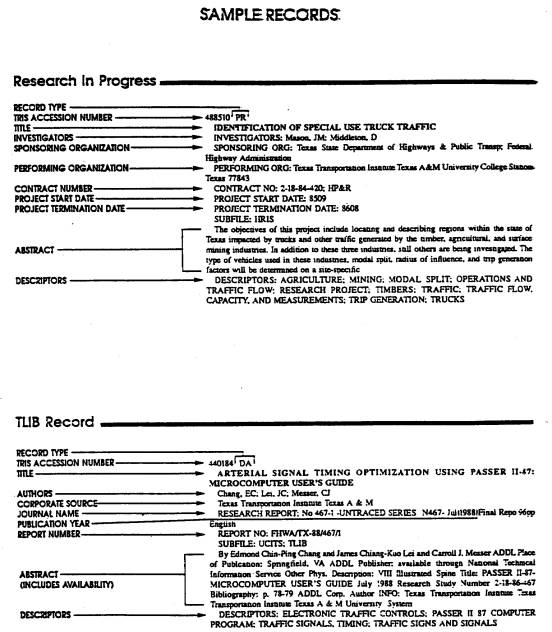

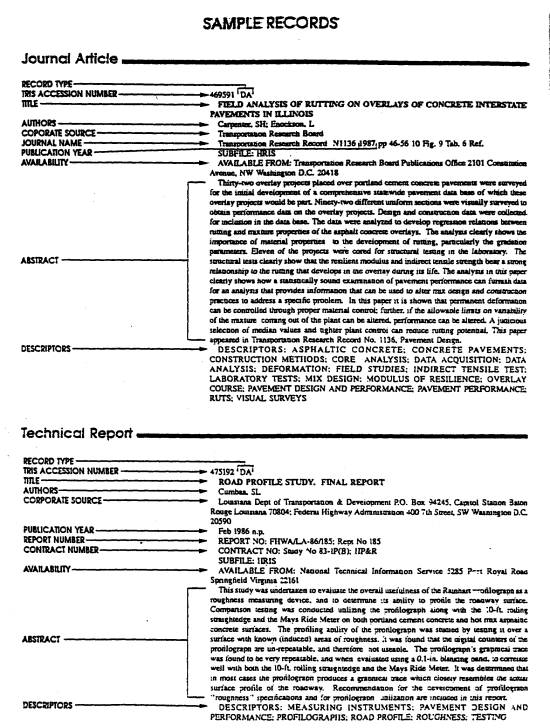

TRIS is the Transportation Research Information Services database, a computerized information file maintained by the Transportation Research Board, and available on-line at the TRB web site. The database contains more than 350 000 abstracts of completed research, and summaries of research projects in progress. The AASHTO Research Advisory Committee Research-in-Progress database is incorporated into TRIS quarterly.

TRIS is available on-line at the TRB web site to perform searches free of charge. The use of TRIS is required by the Federal Highway Administration SP&R, Research, Development, and Technology Transfer Program Management Process. State research units must use the TRIS database for program development, reporting of current RD&T activities, and input of final report information.

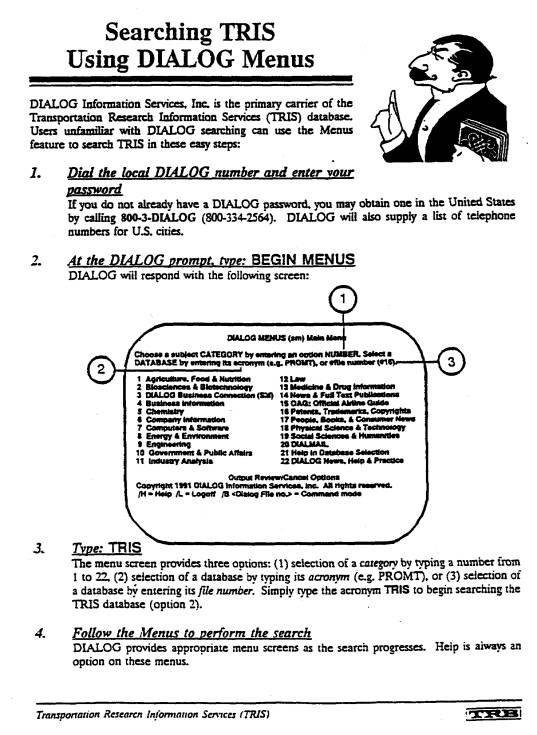

TRIS is the major database for articles related to transportation. A fact sheet on TRIS is given in Figure A-3. TRIS is available in the United States, and many other countries, through Knight-Ridder Information’s DIALOG service (a commercial online database service) as File 63. DIALOG also contains the Transportation Library Subfile (TLIB), which is comprised of bibliographic citations of new acquisitions to the University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Transportation Studies Library, and the Northwestern University Transportation Library at Evanston. TLIB covers all modes of transportation, and more than 9500 citations are added annually.

Figure A-3: Fact Sheet on Transportation Research Information Services (TRIS)

TRIS is also available on CD-ROM as part of a commercial package known as TRANSPORT, which also includes the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) International Road Research Documentation (IRRD) database, and the European Conference of Ministers of Transportation (ECMT) TRANSDOC database. TRANSPORT records can be accessed by using the SilverPlatter Information Search and Retrieval System (SPIRS) software. A two-page fact sheet on TRANSPORT, which includes details of how to subscribe, is given in Figure A-4.

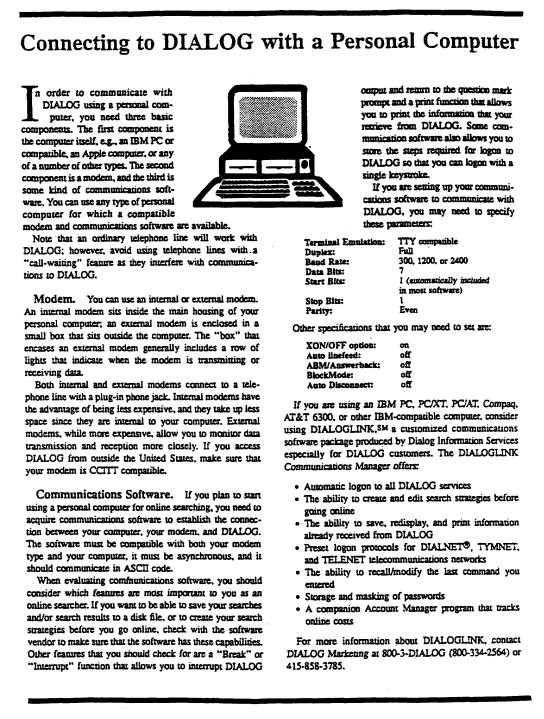

Details about DIALOG can be obtained from DIALOG Information Services, 3460 Hillview Ave., Palo Alto, CA 94304, Tel (800) 334-2564 or (415) 858-3785, Fax (415) 858-7069. Information on connecting to DIALOG with a personal computer is given in Figure A-5 and details of accessing TRIS on DIALOG are given in Figure A-6. DIALOG has international representatives in many countries and these can be contacted through the worldwide headquarters in Palo Alto. DIALOG Information Services Inc. has a home page (http://www.dialog.com) on the World Wide Web, which contains information on products and services. A search of the DIALOG data is only available through the Internet to DIALOG customers. DIALOG is also available through “gateway” services, some of which provide search menus and alternative pricing structures.

TRIS maintains a home page on the Internet’s World Wide Web at the address: http://www.nas.edu/trb/index.html. Users can view a description of TRIS, and, with the correct software, gain access to the catalogs of the two libraries that participate in TLIB: the University of California Institute of Transportation Studies Library (MELVYL), and the Northwestern University Transportation Library (NWUTL). Links to other transportation-related Internet sites are provided, including those of TRB sponsors and government, academic, and other organizations.

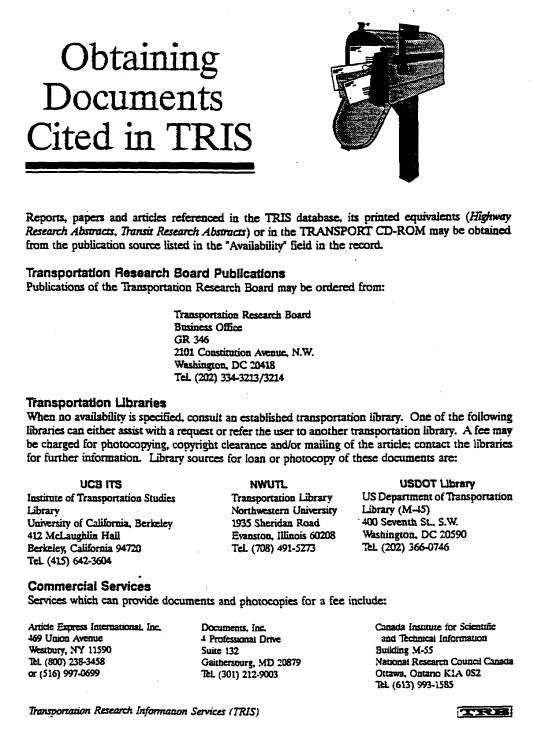

Documents that are cited in the TRIS database may be obtained from the publication source listed in the “Availability” field in the record. Sample records are given in the two-page fact sheet shown in Figure A-7. Additional information on obtaining documents is given in Figure A-8.

Further information about TRIS and service providers is available from: Manager, Information Services, Transportation Research Board, 2101 Constitution Avenue, Washington D.C. 20418, Tel (202) 334-2995, Fax (202) 334-3495.